Last month I traveled home to Davenport, Iowa to visit family. While I was in town, I noticed the traveling Hubble Space Telescope exhibit “New Views of the Universe,” developed 20 years ago and still coordinated today by a team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, where I work, would be at my hometown science museum, the Putnam, for the holidays. Of course, I had to go (and bring the family). So today to start the new year, some thoughts on the importance of science museums and science communications.

The Hubble Space Telescope launched to orbit aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery on April 24, 1990. By the time I was born, eight years later, two servicing missions had already visited Hubble—replacing gyroscopes, solar arrays, cameras and focusing the telescopes initially blurry vision. The fifth and final servicing mission ended eight days after my 11th birthday, giving Hubble some final tweaks and leaving it ready to search the skies for decades to come.

I grew up with Hubble. I remember building my own space telescope from a Quaker oats tube, complete with a wooden dowel to hold cardboard solar panels so my plastic space shuttle could re-enact the servicing missions covered on TV news broadcasts. Watching that huge space plane take off and land, astronauts in their spacesuits using their special tools to fix Hubble way up there in the sky—it was a pretty exciting time to be a kid. I don’t know that I ever wanted to be an astronaut (the Magic School Bus episode where Arnold takes off his helmet on Pluto and freezes into an ice cube may have traumatized me), but I was mesmerized by the stories I saw being told about them.

I grew up with the Putnam Museum, too. It was a favorite haunt as a kid—with its core exhibits depicting Iowa’s prairie and river valley flora and fauna, the IMAX theater’s science movies, and ever-changing traveling exhibits. An anthropology of science class in college complicated my views on the Putnam a bit.1 We read a fascinating article from the Iowa State Historical Society about the museum’s origins in the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences in the mid-1800s. As science was professionalized, the Academy shifted its focus from creating original research to science popularization and elementary education in the early 1900s. That devotion to “lay observations of the natural world” and to reaching young people led to the museum that shaped my interest in science.

NASA has this guiding mantra, “the camera is the mission.” It’s why a custom TV camera was allowed aboard Apollo 11 for a live broadcast of the Moon landing, despite some opposition within the agency (there were only so many data channels available, and TV seemed like a waste to some when there were things like life support and mission control communications to handle). The idea is that none of this science work matters if the public can’t see and be inspired by it.

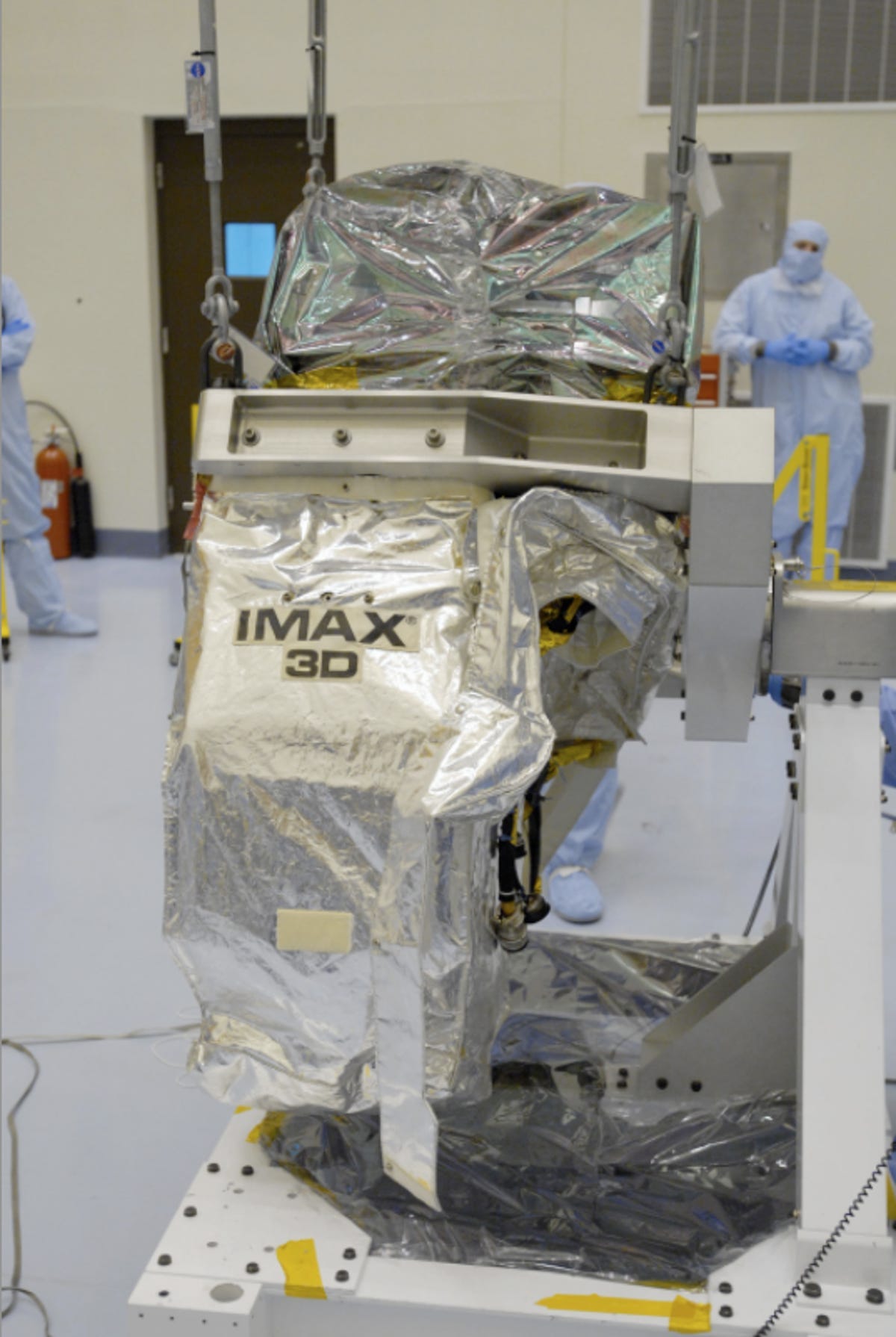

An IMAX 3D camera flew on STS-125, that final servicing mission in May 2009. It was loaded with mile of film, to capture about eight minutes of footage. That footage, interspersed with Hubble images of the universe, became a 2010 IMAX documentary, Hubble 3D. I vividly remember watching it on the big screen theater at the Putnam Museum in 2010. Museum staff gave me a poster that’s still Scotch-taped to my childhood bedroom door today.

When I first walked into the communications office in Building 8 on the NASA Goddard campus in Maryland as an intern, some 12 years after I watched the Hubble film at the Putnam, I was surprised to see the same poster (but nicely framed, not tattered at the edges like mine) hanging on the wall. I asked about it and learned Goddard handled the IMAX camera that flew on that final servicing mission and worked on the documentary.

It was one of those moments that just hit me—after years of stumbling along, following my interests but without a clear picture of what I wanted to do with my life, everything back on the path along the way fell into place, into a clearer narrative. I was here in this place because a lot of people—from my parents to NASA film producers to early Davenport amateur natural historians—made an effort to tell science stories and inspire young people.

Goddard still operates Hubble today. Over in Building 3, just across the street from the communications office, you’ll find the Space Telescope Operations Control Center. It was once staffed around the clock, but since 2011 Hubble’s operations have mostly been automated—no need to monitor data recorders writing onto film or load command sequences to the computers. When my fiancé visited Goddard last fall for the first time, Hubble’s longtime deputy project manager Jim Jeletic gave us an impromptu hourlong tour of the operations center (perhaps unsurprisingly, that’s pretty typical of a NASA scientist—willing to drop everything and share their excitement and passion with strangers even after 35 years working on Hubble). He unlocked his phone and showed us the special app that sends him real-time data from the telescope. If it runs into an issue, Hubble just texts him.

In display cases outside the room and throughout Building 3, carefully labeled parts tell the telescope’s long story—the specialized drill used to take out bolts and catch them so they wouldn’t float away (and many other tools), the camera technology that revolutionized breast cancer imaging, the telescope’s original analog data recorders. It’s like walking into one of the history of science stories I grew up with—guided by someone practiced at retelling them. When Jim started our tour he asked about my partner’s background and adjusted his approach to match—focusing on the science and medical spinoff technologies over the engineering, using different analogies. It was the third or fourth time I’d been on a Building 3 tour and each time it’d been different—designed with care to engage audiences of interns, kids, a medical student.

It’s Hubble’s 35th anniversary this year. At NASA, that means a lot of science communicators worrying over how to mark the anniversary—both reflecting on the telescope’s long, storied history and its remaining years of scientific discovery. How do you get people to care about an old space telescope when there are exciting new ones in the sky, like James Webb? I don’t think we have to be too concerned. Last year we invited Radiolab co-host Latif Nasser and his young son to Goddard. They went on a tour of Building 3 and saw the Hubble control room. The entire day, Latif’s son clutched a Hubble model homemade from cereal boxes and tinfoil-covered plastic bottles. He’d flown across the country with it as his carry on (it had almost been left on at least one flight). At the end of the tour, he proudly presented it to the Hubble scientists.

It makes me wonder how many handcrafted Hubble Space Telescopes are out there. A statement, perhaps, on both the enduring appeal of recycling to kids and Hubble’s power (shaped by thoughtful communicators) to inspire even now, 35 years after it launched into orbit.

At the Hubble exhibit at the Putnam in December it was nice to look back, both into the universe’s early history and my own, and forward. The coming years look uncertain for science communications, with anti-science policies and direct opposition to a free press on the horizon, but no one can stop us from telling good stories and inspiring a kid, somewhere, to get creative with some cardboard.

Reading list

Here’s what I’ve been reading (and listening to) recently (and you might be interested in too):

Trump, the Public, and the Press (Normal Pearlstine, Columbia Journalism Review)

“Billionaires, once thought to be the saviors of journalism, are proving themselves poor stewards of media companies.” A good (and frightening) read on the relationship of billionaire media owners with facts, the truth and Donald Trump.

An Elven Alliance Is Protecting Iceland’s Natural Wonders (Kaja Brown, Atmos)

In Iceland, environmental activists have long used the country’s belief in Huldufólk, elves, to promote land conservation. Whether or not the elves exist (and 62% of Icelanders say they might), they’ve helped stop destructive projects—people have protested successfully to protect elf land and culture. “Everyone is aware that the land is alive, and one can say that the stories of hidden people and the need to work carefully with them reflects an understanding that the land demands respect.”

Climate Models Can’t Explain What’s Happening to Earth (Zoë Schlanger, The Atlantic)

Zoë is so great at taking on big issues in science in a straightforward, comprehensive way. And this is a big one that comes up in almost every interview I do with paleoclimate researchers and climate modelers. It’s really hard to make those models agree. Most of the time, they underestimate warming. We’re repeatedly taken by surprise. Why?

Charles E. Putnam, the museum’s namesake and a member of the Academy, was embroiled in a national debate of the veracity of relics taken from “mound-builder” archaeological sites throughout the region.