Science, industry and government, oh my!

Some thoughts on how we can better tell stories about the ways money, politics and science intersect

Hello! I have a new story out this week on Smithsonian Magazine’s site—it’s a deep dive into the intertwined economics, politics and science of deep-sea mining in Norway. I hope you give it a read. The newsletter today gets into some of the same themes.

At the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, a favorite childhood haunt of mine, basic science research and industrial achievements are celebrated equally—you can peer into a Gemini space capsule or ride an elevator into an underground coal mine, depending on your mood. Journalism likes to treat science and industry (sometimes we say jobs or the economy) as distinct beats. But their history (plus that of government, which we throw into another separate bucket called politics) is deeply intertwined.

Take space, a topic I cover a lot. It’s no secret the U.S. space program poached German rocket scientists (who, let’s say, were not originally focused on exploration) after World War II. The first NASA astronauts rode ballistic missiles into orbit—which could have easily carried more explosive payloads. NASA, which now conducts critical research on Earth’s climate, owes its existence to a space race that was more about geopolitics than science.

Or take paleoclimate science—the first ice cores, which revolutionized our understanding of ancient climate conditions and made climate models possible, came out of a failed Cold War-era U.S. military project to tunnel nuclear missile silos into the Greenland ice sheet (NASA research flights actually rediscovered the base last year). And there’s a lot of similarities between the technologies that made drilling for climate secrets in rock and ice and drilling for fossil fuels possible. And speaking of fossil fuels, it was paleontologists, ones specializing in tiny ocean fossils, who made it much easier for companies to find and drill for oil.

Anyway, those two examples—space and ice cores—seem particularly relevant right now, with Donald Trump obsessing over Greenland’s natural resources and strategic military/geopolitical importance (as its ice sheet climate records melt away) and Elon Musk pushing for more SpaceX military contracts and big changes to NASA’s science and exploration goals. Government funds science, science fuels industry, government cuts science, industry profits from government?

This complicated triangle, with science, industry and government at its vertices but also, somehow, overlapping, has been at the heart of a lot of the stories that have interested me recently. There’s the debate over carbon sequestration in the Midwest, which I wrote about for Undark. When the only labs studying geologic carbon sequestration are funded by the oil industry, which also established the field (funding conferences, journals and entire university departments) in the first place, can we trust the scientists doing the work (I spoke with a rare scientist not funded by the industry for this newsletter a while back who says absolutely not)?

This didn’t make it into the Undark piece, but one thing that struck me in reporting it was that scientists on both sides of the debate—environmentalists who want to stop carbon sequestration in its tracks and industry-funded scientists who want to prove it’s safe—brought up Flint, Michigan as an example. In question in this story was whether injecting liquified carbon dioxide underground beneath an aquifer is safe. The same science, the same data, even the same case studies can be used to make opposite points. Navigating those perspectives (and adding my own, since that piece was an op-ed) was hugely challenging.

There’s another layer here. The carbon sequestration industry is booming in the Midwest as a solution to emissions from corn ethanol, a biofuel. Depending on how you crunch the numbers—and how you crunch them as a scientist probably depends some on who’s funding your work—you can find that ethanol has higher or lower carbon emissions than gasoline, and scientists have indeed found both. Both sides have accused the other of cherry-picking data and making worst-case assumptions in their models. There’s a lot of wiggle room in calculating the emissions from ethanol—do you include the trucks that move corn from the farm to the plant? The emissions from producing the fertilizers and herbicides farmers use to grow that corn? The oil and gas industry and the agriculture industry both have huge stakes here and an interest in pushing the research one way or the other. And the government has a key role too—as with carbon sequestration, it gets to pick the winners and losers by incentivizing certain practices and banning others.

But how do we cover all that complexity as journalists? How do you solve (or even just write about) a problem like carbon sequestration, where the science is so muddied? How do we address, in our stories, who’s funding the research? I rarely ask a paleontologist I’m interviewing about a new finding where their money comes from. Should we even address research funding in stories, when so much of the general public is already disinclined to trust scientists? We need to point out bad science, of course, but can we do that without discrediting Science (with a capital S)? And then maybe a bigger question—what happens when the government pulls away from funding research (which is happening right now), and industry moves in to fill the void? History tells us industry won’t fund science it doesn’t see profit in. What does that mean for the science that does get funded and the degree to which we should trust it?

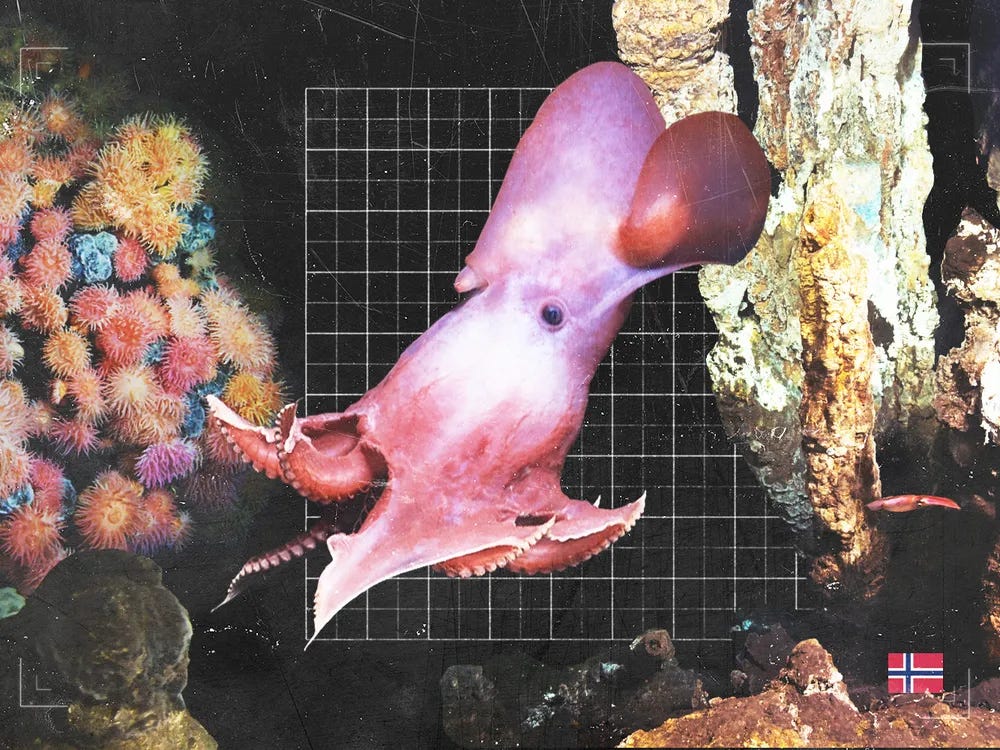

I’ve been thinking about all this a lot recently because for something like six months now I’ve been working on a digital feature for Smithsonian Magazine about deep-sea mining in Norway. I first got interested in Norway back when it looked like it would be the first nation in the world to open its seabed to mining. In December of last year, they put off the first licensing round indefinitely amid public pressure. But companies are still exploring deep-sea mining in international waters, and Trump is pushing for it.

In interviews with historians, economists and deep-sea ecologists and geologists, I started to run into stories that brought me some hope—cases where scientists working for oil companies used their positions to advance deep-sea research and push for conservation when academic researchers could not, and where small-scale fishermen enlisted government science institutes to protect ecosystems against large-scale trawling. Those stories, I think, could be a lesson for the rest of the world as we cautiously approach a new natural resource frontier (or, perhaps more likely, charge headlong into our next Malthusian Swerve). Norway’s history shows it’s possible to navigate that wobbly, confusing triangle, with its varying and contradictory incentives and goals. Industry, government and academic science can coexist and work together—at least in Norway, a smaller country with a different cultural history than our own. But hey, hope is hope.

Reading list

What I’ve been reading recently (and you might be interested in too):

The Decline of Outside Magazine Is Also the End of a Vision of the Mountain West (Rachel Monroe, The New Yorker)

This is a great long read about the sad fall of Outside magazine. How to turn a once-mighty journalism outlet for great stories into a NFT-peddling tech startup grift.

About That ‘Possible Sign of Life’ on a Distant Planet (Ross Andersen, The Atlantic)

The big science story of the week was a “possible signature of life” on a planet called K2-18b. As Ross writes, “possible” is doing “Atlas-like” work in that headline. I was looking for a good, realistic take on what the new study means (not a lot) and I like how Ross also takes on the way we get this kind of news—an overpromising push notification that most people don’t actually tap anyway.

Is this really a dire wolf? Here’s how the ‘de-extinct’ pups compare to the real thing (Riley Black, National Geographic)

OK, there were two big science stories of the week. When the “de-extinction” of the dire wolf news broke online with a shiny (and, frankly, embarrassing) feature in Time magazine, I saw Riley Black immediately start posting on Bluesky. No, the dire wolf has not been de-exctinct-ed. And this corporate distraction is already being used by the Trump administration to justify rolling back endangered species protections. So I was glad to see Riley write this Nat Geo piece setting the record straight.