This week I’ve been deep in the fact-checking process for a 4,600-word feature story on cold-water corals that I’ve been reporting for Hakai magazine since May. It’s the last step (save for copyediting) in the VERY long (but rewarding) process of publishing a feature. Fact checking doesn’t work the same way everywhere, but Hakai is a pretty representative example, I think. So today I thought it might be fun to follow a fact and see what all goes into getting everything right in a story like this one.

First, the process

After three or four rounds of edits, my feature story was “done”—that is to say, my editor and I weren’t planning on making any other substantive changes to the content and organization of the piece. The next step was annotating it for fact checking. Most magazines/web outlets these days don’t have in-house fact-checkers—they hire freelancers to check their stories (written by other freelancers, like me). And they only do it (because it’s an investment) for big feature stories, not news pieces. For those, the fact checking is typically up to you.

To make things as easy as possible for the fact checker (whom I did not meet), you annotate all the facts in your story before handing it off to them. Some publications want you to do this with comments in Microsoft Word; others prefer footnotes. Either way, the process is the same. Every piece of information gets an annotation. Did it come from a study? You link that study (and if you’re feeling very kind, the page number in that study). Did it come from an interview? You link the transcript and audio file. Does a photo you took confirm what you saw in the field? You refer the fact checker to the relevant images. Did you check a fact via email? A PDF of that exchange goes to the fact checker.

Annotating a longish story like this one can take a very long time. You can set yourself up for success by doing some of this work along the way—keeping track of which interviews contained which information, carefully organizing downloaded research papers in one place, etc. as you write. Regrettably, I am very bad at doing that, which means much more work down the line as I frantically try to find the right bits of information to back up the claims made in the story while sifting through many more interviews and research papers full of information that didn’t make the cut. I just checked, and for this story I have 72 PDFs of research papers and 61 interview recordings in Otter (most of those at least an hour long).

Once you’ve annotated your draft, it goes to the fact checker. Then, you wait (in my case, for several weeks) as the fact checker goes through everything. For facts that come from websites or research articles, it’s a simple matter of making sure you translated the science correctly and didn’t get any institutions/names wrong. For information that comes from interviews, it’s a little trickier. The fact checker has to get ahold of your sources to make sure they stand by the quotes you’ve chosen. That can be a challenge if, say, your sources live in a remote fjord in Chilean Patagonia with limited access to cell service/internet.

Then, you get your draft back. And it tends to come bearing questions… things the fact checker couldn’t easily confirm, phrasings experts weren’t happy with and so on. It’s on you (and your editor) to address those problem spots to finish out the fact checking process.

One finicky fact

I thought it might be helpful to share a specific example. To set the stakes of my story on deep-sea corals, I needed to describe how much damage human activity has already caused to seabed ecosystems. I had some great quotes from scientists, but putting good numbers on the scale of the damage, mostly from trawl fishing, turns out to be pretty difficult.

Here’s a sentence from my original draft, when I sent it off for fact checking:

Today, trawling has impacted at least 14 percent of all continental shelves and slopes at or above 1,000 meters, scraping thousand-year-old coral gardens off the tops of seamounts in minutes to capture the fish hiding within them.

I accidentally connected this fact to the wrong research papers in my annotations, which got me this response from the fact checker:

To verify this data, the journalist shared two papers. However, neither of these texts mentions the percentage of impact from trawl fishing…I asked Roberts, and he said he had no idea where this 14% comes from.

Oops. I quickly figured out where that number had come from—an interview with coral researcher Michelle Taylor (not Murray Roberts, whom the fact checker spoke with), who attributed it to “a recent paper” in our recorded conversation. I quickly found that paper (Amoroso et al., 2018 in PNAS), which I should have done while annotating the story—but in a longish piece like this inevitably something (embarrassingly) falls through the cracks.

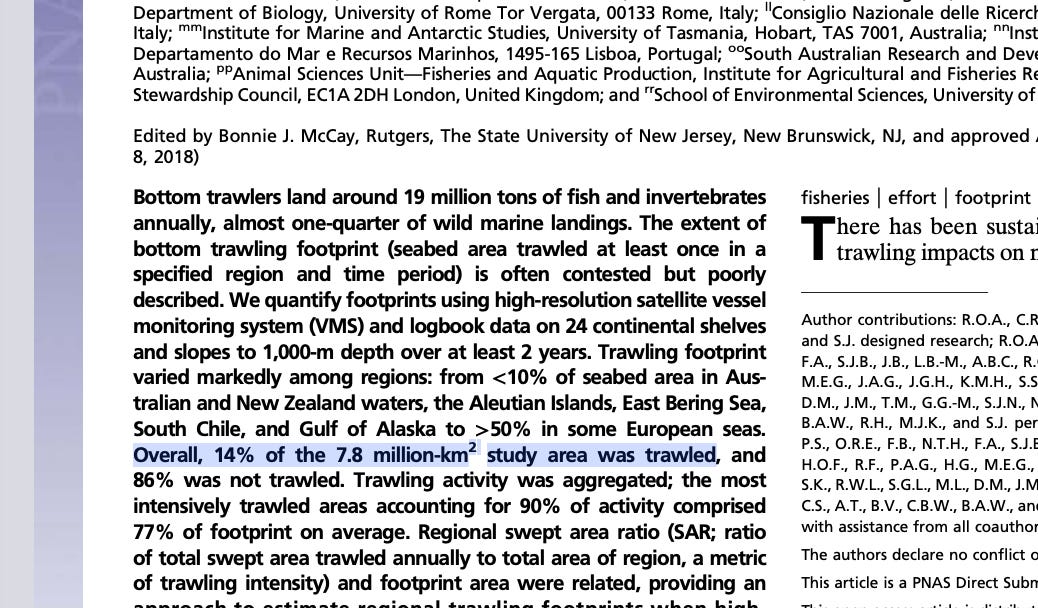

There it is: “Overall, 14% of the 7.8 million km2 study area was trawled.” But OK, what does that actually mean? Reading the rest of the paper, that 14% trawled was within the multiple study areas, broken up across the world. The percentage trawled varied a lot geographically—barely any of the Alaskan continental shelf had been trawled, while nearly 70% of the Adriatic Sea had been. And also, the total area of seabed is 361 km2, way bigger than that study area. Plus, it’s a 2018 paper. So I kept looking. I wanted a second source.

I then found a more recent paper (Sala et al., 2023 in Nature) that estimated 5 million km2 of seabed is trawled annually. That’s about 1.4% of the total seabed. But trawl fishing only happens on continental shelves shallower than 1,000 m, which is about 10% of the world’s seabed. With 37% of seabed theoretically trawlable, that percentage comes up to 13.5%. Which is pretty darn close to the 14% estimate in the earlier PNAS paper Taylor mentioned.

A few hours down the drain… but I put all that info in a comment, and together my editor and I tweaked the sentence the fact checker had flagged as follows:

Today, scientists estimate trawling impacts nearly 14 percent of all continental shelves and slopes shallower than 1,000 meters. With modern gear, trawlers can scrape thousand-year-old coral gardens off the tops of seamounts in minutes to capture the fish hiding within them.

Those might seem like tiny tweaks, but they’re the kind of edits that button up facts for publication, keeping you and the outlet safe. Here’s another example, from a second about cold-water coral conservation:

In the absence of oceanwide maps, they defined the niche in which cold-water corals can live, based on data about ocean currents, water productivity, chemistry, and temperature, and fed that data into models to predict where corals should be. Those maps led the U.S., Australia and New Zealand to close large areas to fishing to protect corals.

Roberts (one of my sources that the fact checker talked with), took issue with that framing—in reality, predictive maps of corals led to actual discoveries of corals in specific places, which were then followed by advocacy efforts that led to the fishing area closures. It wasn’t a straight shot from predictive maps to fishing closures. My editor suggested an easy fix:

In the absence of oceanwide maps, they defined the niche in which cold-water corals can live, based on data about ocean currents, water productivity, chemistry, and temperature, and fed that data into models to predict where corals should be. In places where corals were found to be actually present, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand closed large areas to fishing.

The lesson here is that you don’t necessarily need to get into all the complexities and nuances to get the facts right. This paragraph did not need a long explanation of advocacy or specific examples to be effective/true. Sometimes, simpler is better. Even if there’s a lot of unseen work behind the scenes and a lot of detail in comments that leads to those much simpler, safer sentences.

Reading list

First, a few fact-checking resources today:

The Chicago Guide to Fact-Checking, Second Edition (Brooke Borel, The University of Chicago Press)

If you’d like to learn how fact checking works (from the perspective of both the checker and checkee) from someone more eloquent than I, Brooke Borel’s book is the definitive guide. She also happens to be a phenomenal editor who’s guided a couple of my feature stories through the fact checking process at Undark magazine.

Factual (Wudan Yan)

Wudan Yan is sort of a journalism jack of all trades. She’s a narrative writer, a podcast host and producer, and a fact checker (for magazines, books, podcasts, etc.). She makes a great podcast on the business of freelance writing called The Writers’ Co-op, but she also recently launched her own fact-checking agency, called Factual. It’s the first of its kind and works like a “dating app” for fact checking, matching journalists with fact checkers. And I think they’re hiring?

Now, what I’ve been reading (and listening to) recently (and you might be interested in too):

Going Deep: The Perils and Promise of Long Science (Christopher Pollen, CIOOS Pacific)

I spent last week at the National Association of Science Writers annual conference in Raleigh, NC, and this piece won a NASW Institutional Science Writing Award there. It’s a great long read about the challenges inherent in long-term research. To better understand Earth’s complex systems, scientists need to study them for a long time. But science as an institution just isn’t set up to make that easy.

Chasing ghost particles (Corey S. Powell, aeon)

Also at the science writers conference, I briefly met the physicist Hitoshi Murayama, who gave a very fun talk on theoretical particle physics for an audience of journalists. Then, I happened upon this very relevant and well-written story on the mysteries of neutrinos.

The Lizard King of Long Island (Ben Goldfarb, The New Yorker)

Ben is always a must read, and this wild story is no exception.

How Wisconsin Lost Control of the Strange Disease Killing Its Deer (Jimmy Tobias, The Nation)

I’ve sort of been doom reading a lot of coverage of bird flu/H5N1 and our complete inability to prepare for future zoonotic pandemics. So this was a depressing (but compellingly reported!) read. A prion disease is ripping through deer across the country, threatening to end hunting as we know it. Also, it could (potentially) infect us.