An Earthrise Christmas 🌎

Some throwback thoughts on science communication and the power of imagery

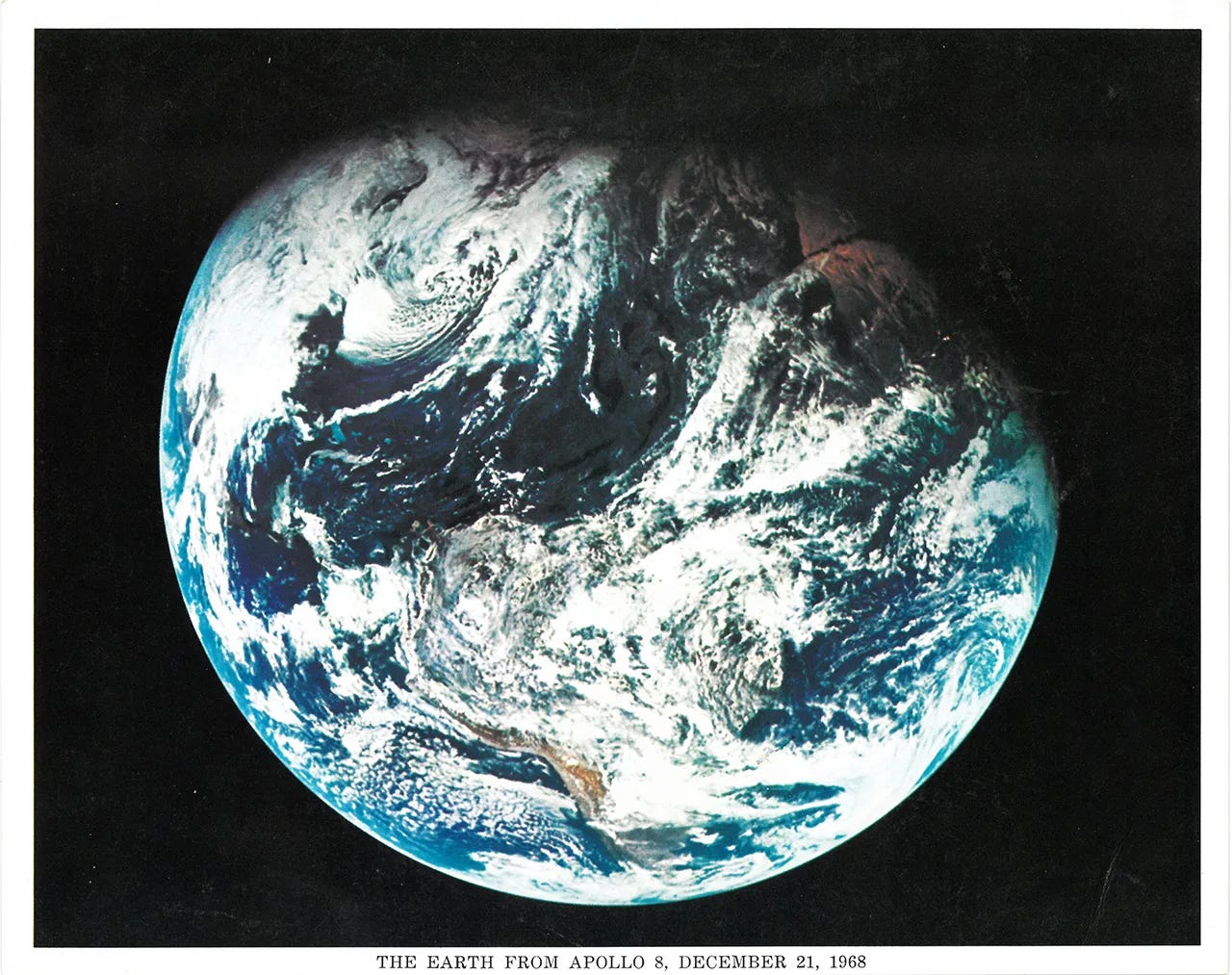

My family has a tradition of giving each other Christmas ornaments every year. This year, I received this one:

And hanging it on the tree, I remembered quite suddenly a moment in 2017, back when I was a newly declared cultural anthropology major at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. Science and environmental journalism wasn’t on my radar as a career. I was still getting over my initial plan to study computer science (my heart was definitely not in it). I certainly didn’t expect that some seven years later I’d be writing for science magazines and producing podcasts for NASA. But that moment in 2017 was the one that set me on this very different trajectory.

I was sitting in my advisor’s office. I’d just written a paper for his anthropology of science class about Earthrise, the famous photo of Earth rising above the lunar surface taken on Christmas Eve by the Apollo 8 astronauts as they orbited the Moon. I had gotten pretty into the research. I remember talking about the story with my family to such an extent that my partner started jokingly referring to the piece, which I’d titled “Earthrise: How a Photo from Space Sparked a Green Revolution” as “Earthrise: The Most Important Photo Ever Taken By Anybody Ever.”

My advisor saw something in that paper that I didn’t—a passion for writing stories that go deep and draw on multiple disciplines to explain the world. I remember him pulling out a printed, marked up copy and saying, “You know, I could see you sitting at the science desk at NPR someday, or writing for a magazine or something.” We’d had a lot of discussions about what I could do after college. But that image of a paper-strewn desk in a newsroom with reporters running around making phone calls stuck with me. And I started to work towards it, although I didn’t really know how.

So after I hung that NASA Earth ornament on the tree this month, I dug around on my many disorganized hard drives full of projects and eventually found the Earthrise paper. It’s not great, in retrospect, but in it I do see the seeds of my interests in writing, in science history, in space, in environmental conservation. And now here I am at the end of my second full year as a science journalist, feeling very lucky to be writing every day, working on an Earth science series for NASA and hopefully, in a few short years, covering Artemis II—really Apollo 8 part two, another mission to orbit the Moon that will without a doubt give us a new Earthrise image. So, in honor of Earthrise, which is a Christmas story, of course, I thought I’d publish the paper here today.

Earthrise: How a Photo from Space Sparked a Green Revolution

At 7:50 a.m. on December 21, 1968, Col. Frank Borman, Capt. James Lovell, and Major William Anders sat strapped into the Apollo 8 command module high above the new Saturn V rocket at Cape Kennedy, Florida, prepared to soar into the sky on the first manned voyage to the Moon. The countdown completed, and 7.5 million pounds of thrust sent the 36-story rocket violently toward space.

As the capsule reached Earth orbit, Commander Borman told flight engineer Anders if he caught him looking out the window, he would fire him. Earth was the thing underfoot, after all—a mere distraction for the busy crew. With the pressure of the space race driving the mission, the focus was firmly on the Moon. After a three-day drift 240,000 miles away from home, the Earth growing smaller as its giant gray satellite drew ever nearer, Anders made the careful maneuvers navigating the command module into lunar orbit. For three orbits, the spacecraft swung around the Moon, and the crew spent their time on live TV broadcasts and taking planned photographs of specific areas of the Moon.

By chance on the fourth orbit, after a slight orientation change, Borman caught sight of an amazing image. “Oh, my God, look at that!” he shouts on the mission recording. As Anders later said, discussing the view, “And up came the Earth. We had had no discussion on the ground, no briefing, no instructions on what to do.” Anders joked that a photo of the Earth rising over the lunar surface wasn’t on the flight plan, “…And the other two guys were yelling at me to give them the camera, I had the only color camera with a long lens…They were all yelling for cameras, and we started snapping away. The results were a few monochrome images from black and white film magazines in Borman and Lovell’s cameras, and a full color frame of the “blue marble” of Earth contrasted sharply against the Moon’s desolate gray surface that would ignite a revolution and be remembered by history as one of the most influential photographs ever taken. They called it Earthrise.

Later that night the astronauts turned their TV cameras toward the Moon’s surface and began their scheduled live Christmas Eve broadcast from orbit. Millions from around the world watched as three men 240,000 miles away shared images of the Moon and their unique view of planet Earth as they took turns reading from the book of Genesis. Gazing at the distant blue world, Lovell said, “The vast loneliness up here of the Moon is awe-inspiring. It makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.” That realization was the key. Apollo 8 was meant to show Americans the Moon and pave the way for future missions to its surface, but the real gift Lovell, Borman, and Anders gave the world that Christmas Eve, 1968, was Earthrise, a single image of our home taken from very far away.

Days later, the command module splashed down in the Pacific and the Earthrise film was taken to a darkroom, hand developed, printed, hung, dried, then revealed to the public. As Jeffrey Kluger, Editor at Large of Time Magazine writes, it was “nothing more or less than a photo of home—and it was like nothing the human species had ever seen before.” As Bill Anders reflected, many years later, "We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” The photograph’s power and longevity came from its unique and inspiring new perspective on what our planet is—not a massive, indestructible mass of rock and plants, but an exquisite and fragile sphere floating in the blackness of space. That is the realization that sparked a revolution.

An Earth in crisis

Although it was Christmas week when Borman, Lovell, and Anders took their famous photos from the Moon, all wasn’t idyllic back home—around the world chaos and unrest reigned: pollution ran rampant, unchecked by the government, and Kluger adds, “Southeast Asia was in flames, Czechoslovakia was living under a Soviet crackdown, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King had been murdered and cities across the country had been torn by rioting.” As Vesla Weaver, professor of Politics at the University of Virginia writes, “In 1968, two-thirds of the public believed the police should shoot looters to kill…the country was moving towards two societies – one black, one white.” With so much political and social unrest across the country and world, Americans were desperately in need of some good news.

Years earlier, in 1961, President Kennedy, in a famous speech, had promised to put an American on the Moon by the end of the decade. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first person in space a month earlier, “greatly embarrassing the U.S.” In his historic speech before a joint session of Congress, Kennedy implored legislators to help the country “catch up to and overtake the Soviet Union in the space race.” By 1968, the decade was drawing to a close and the United States was no closer to landing an astronaut on the lunar surface. As space historian and author Piers Bizony writes in his article “The Politics of Apollo,” after Kennedy’s assassination, the “challenging technological feat” seemed even less likely to be achieved before 1970.

It was not for lack of trying—NASA was a beacon of hope in difficult times, employing 40,000 Americans in dozens of facilities, and contracting over half a million more to work on the Apollo missions. In addition, the program worked to improve education through NASA-related programs. Despite the billions in resources and feverish research poured into the space program, NASA was not ready to send astronauts to the Moon. The Apollo missions had not been universally successful—in 1967 Apollo 1’s design had been rushed, and a series of failures had caused the death of the entire crew during a launch pad simulation. After five unmanned launches in variations of the Apollo 1 command module, NASA was ready, a year later, to again send men into space. Apollo 7 launched in October, 1968, catapulting three astronauts into low-Earth orbit atop the Saturn 1-B rocket. A few months later, Borman, Lovell, and Anders were selected for a very similar mission to test the new Saturn V.

The great lunar gamble

NASA scientists never planned to send Apollo 8 around the Moon. The “lunar hardware was still unproven,” and Apollo 8’s intended mission was simply to test new equipment in a low-Earth orbit. That month the CIA informed NASA, however, that the Soviet Union was in the process of preparing its own manned lunar mission. As NASA scientist and author Bob Granath writes in his article “Astronaut Photography from Space Helped 'Discover the Earth,” NASA then made what was later dubbed by a senior NASA official “the boldest single decision that the agency ever made”—to redirect Apollo 8 to lunar orbit. Until that point, human beings had only traveled a few hundred miles into space. It was a “gamble to say the least”—the command module still had flaws and instrument failures, and, as NASA author Brian Dunbar writes in “Apollo Astronaut Shares story of NASA’s Earthrise Photo,” the Saturn V was untested.

Despite concerns from the press and a nervous atmosphere at ground control on December 21, the launch was a success and Apollo 8 became the first manned spacecraft to exit the Earth’s orbit. A few days later, Anders would be in position to take the famous photograph, thanks to the political pressures of the space race and rushed planning of NASA scientists. The mission was both a scientific and resounding cultural success. Robert Godwin writes in the foreword to his compilation of Apollo 8 mission reports, “All the wars and riots and vendettas were thrust briefly into perspective and the people of the planet Earth were shown to be one species on a small blue gem adrift in a black forbidding sea.” As one citizen wrote to the crew later, “You saved 1968!” Americans got the good news that they so desperately needed.

An Earthrise Christmas, a Silent Spring

While extremely influential, Apollo 8’s Earthrise was not the first step in the national environmental movement. As Elim Papadakis writes in his work Historical Dictionary of the Green Movement, in 1962, Rachel Carson published her famous work Silent Spring, one of the first books which provided an “articulation of the discovery that the quality of human life could be seriously threatened by certain types of economic growth and forms of industrial development. In her book, Carson shared with Americans the disturbing impact of DDT (chloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) and other chemical pesticides on wildlife, habitats, and humans. More importantly, however, she “challenged the entire approach of the chemical and other industries,” and “their ‘arrogance’ in assuming that ‘nature exists for the convenience of man.’”

Despite the efforts of the chemical industry, the book was widely published and disseminated. As Benjamin Kline writes in First Along the River, A Brief History of the U.S. Environmental Movement, “[Silent Spring’s] passionate warning about the inherent dangers in the excessive use of pesticides ignited the imaginations of an enormous and disparate audience.” Americans were outraged and concerned for the extinction of “treasured symbols like the bald eagle.” While other scientists had published findings about the dangers of DDT, Carson had the ability “to place scientific discoveries in the context of a fundamental questioning” of how people considered their own environment.

In response, President Kennedy established a special panel of the Scientific Advisory Committee, and the government supported Carson’s claims. The administration proposed the Land and Water Conservation Fund and Clean Air Act in 1963, appropriating federal funds to conserve waterways and attack air pollution. Silent Spring made Americans aware of the global environmental crisis, and inspired people to think about their place in the environment differently. Six years later, the Earthrise photo would fuel the flames of the fledgling environmental movement that Carson ignited, and inspire people to think about their place in the world. As British Environmentalist Michael McCarthy writes in his article “Earthrise: The Image that Changed Our View of the Planet,” The Earthrise image “crystallized and cemented the sense of the planet’s vulnerability which silent Spring had awoken six years earlier.”

Spaceship Earth awakens

In 1965, in an address to the United Nations, U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson first described the idea of the “Spaceship Earth.” Our planet, he explained, is like a spaceship flying through the void of space—we are reliant on our natural surroundings and “we should be aware of the consequences of disregarding our need for resources like air and water” by exploiting and abusing the environment. A year later, economist Kenneth Boulding expanded the concept in his essay “The economics of Coming Spaceship Earth,” in which he drew on the popularity of the space race, drawing a contrast between “a ‘cowboy’ economy based on production consumption, and exploitation…and a ‘spaceman’ economy…maintaining the quality and complexity of the total capital stock.” The Spaceship Earth concept grew in popularity with the visual evidence of The Earthrise—truly, the nation realized, we do live on a Spaceship, and its name is Earth.

By the mid-1960s, environmental groups began to mobilize—The Sierra Club, led by photographer Ansel Adams, and the Friends of the Earth group were formed to rally against environmental exploitation, using the Earthrise photo as a symbol. As author Kirkpatrick Sale writes in The Green Revolution, Young people, already gathering to protest the Vietnam war and support the civil rights and feminist movements, flocked to the cause. Opinion polls in 1970 showed that in just five years, the number of Americans who rated air and water pollution as one of the three major problems facing the nation rose to 53%. Following LBJ’s exit from the white house, Nixon, in his 1970 State of the Union address proclaimed that the 1970s “absolutely must be the years when America pays its debt to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters.”

The idea of a global community concerned with an entire planet’s environment spurned on by the Earthrise photo had far reaching effects—the movement culminated, for example, in the first Earth Day celebration, April 22, 1970, in which 20 million Americans took part. The “Earth Day” holiday was planned by Senator Gaylord Nelson, a conservative from Wisconsin, with the goal of “captur[ing] the spirit, if not the politics, of the “sit-ins” of the fractious 1960s.” Earth day was a huge success. As the Earth Day Network website reports, “In 1970, the year of our first Earth Day, the movement gave voice to an emerging consciousness, channeling human energy toward environmental issues.” Earth Day, and the environmental movement in a larger sense, “took place largely as a result of the efforts of former antiwar and civil-rights activists.”

Inspired, in part, by the Apollo photographs, in 1970 James Lovelock, a British scientist working for NASA, proposed the Gaia hypothesis—that earth was “a self-regulating system in which living matter collectively defines and maintains the conditions for the continuance of life.” He took the term from Greek mythology, in which Gaia is the personification of Earth—the ancestral mother of all life. The hypothesis concludes that nature will survive the “onslaught on it by human beings,” but human beings may not withstand nature’s response to the assault. The revolutionary book combined scientific study with an appealing mysticism—as Michael McCarthy notes, “If Earthrise is the Green Movement’s iconic image, Gaia might be said to be its sacred text.” Like the book, the famous image of the blue marble on which we all live and depend is certainly at once a mystifying image and an urgent message for conservation.

Also in 1970, the Nixon administration established the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, in response to “elevated concern about environmental pollution.” Following its creation, the agency acted quickly, passing the Clean Air act, which imposed new restrictions on industries regarding air pollution, lead paint restrictions, chemical pesticides restrictions, and a leaded gasoline phase out. Since its establishment, the EPA has been the main governmental power “safeguarding the air we breathe, water we drink, and land on which we live.”

Remembering Earthrise

Seven months after Anders took his famous photograph, Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the Moon and echoed Apollo 8’s sentiments. Standing on the lunar surface, he blotted out the Earth with his thumb. As journalist Rob McKie writes in his article “The Mission that Changed Everything,” when asked if the action made him feel “really big,” he responded, “No, it made me feel really, really small”.

With Apollo fading to the distant past, it’s important to realize that the missions and Earthrise photo was not NASA’s only contribution to the environmental movement. As NASA writes on their site, “Since its inception in 1958, much of [the organization’s] work has focused on studying Earth and better understanding weather, climate and the forces that make a difference in people’s lives around the world.” Throughout history and still today, NASA’s work in Earth science affects people around the world—improving our ability to realize climate problems, and respond to natural disasters. NASA has launched numerous satellites in recent years dedicated to climate research, such as Landsat, Jason-3, the Deep Space Climate Observatory (or DSCOVR), and Soil Moisture Active Passive, which have contributed to “improved environmental forecasts, [a] better understanding of natural hazards, and help [for] researchers [in] determin[ing] ways to enhance utilization of Earth’s resources.

Though the Apollo 8 photograph was born out of a mission driven by conflict, its effect was one of profound international unity. The idea that we all share a fragile planet that drove the environmental movement has also driven the space program. Though NASA has never received the funding or attention it did during the Apollo years, the program continues in its mission to explore space and expand our understanding of Earth. Today, the International Space Station, or ISS, is a symbol of international unity and cooperation. As the NASA writer Mark Garcia writes on the ISS webpage “International Cooperation,” the program’s greatest accomplishment “is as much a human achievement as it is a technological one.”

The space agencies of the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, Canada, cooperated and to build (and now to maintain) the station, which continues to orbit as a beacon of hope for international peace and collaboration. The days of fierce competition of Apollo are over. As Dr. Christopher Riley writes in his BBC article “Happy Birthday Earthrise,” though only 24 human beings have ever laid eyes on the Earth in its entirety from the vantage point of the Moon, the many astronauts who see our planet from the low-Earth orbit vantage point of the ISS still feel the same way as Borman, Lovell, and Anders did almost fifty years ago. As Expedition 26 and 27 astronaut Cady Coleman said in 2012 of her own view of the planet from orbit, "When you see our whole planet like this, you realize we are altogether citizens of the world." NASA astronaut Rob Garan shared a similar perspective in 2012: “When you see the beauty of our planet, it is striking, it's sobering. For the 50 years that we've been flying humans in space, astronauts and cosmonauts have always commented about how beautiful, how fragile and how peaceful our planet looks from space. Seeing this from space really had a big impact on me.”

Now, in 2017, as we look forward to future space exploration to other interstellar bodies, funded either by NASA or private corporations, we must keep in mind the message of Earthrise. As Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan writes on the Sapiens blog, to survive in space “we will need to cooperate and pledge to help one another.” A society, he continues “that refuses to protect our habitat, rejects the diversity that makes us most innovative and adaptable...is not a society ready or able to move into space.” Our voyages into space gave us Earthrise, and remind that we are all passengers on the original spaceship, spaceship Earth, which we must maintain with as much care and precision as any other delicate craft.

On what is nearly the fiftieth anniversary of the famous Earthrise photograph, it is important to remember not only the history of the environmental movement it started, but what it represents. In his book Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth, Robert Poole writes, “Looking back, it is possible to see that Earthrise marked the tipping point, the moment when the sense of the space age flipped from what it means for space to what it meant for Earth.” In his article McKie quotes T.S. Eliot “We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

When Americans saw, through their fuzzy TV sets, the Earth rising above the lunar horizon, they saw the place where they started for the first time. We have the Earthrise photo and the tale of the Apollo missions (Aptly named for the god of healing, light, and truth) to thank for this most important realization of exploration. In Life Magazine's "100 Photographs that Changed the World" edition, photographer Galen Rowell called the Earthrise photo, "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken.” It was an unplanned photo, of a subject seen by chance, but it will live on as a symbol of the green revolution, and the fragility of the planet Earth, our Gaia, our only home.

Happy holidays! 🌎🎄